Asuntos Tradicionalistas

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Misa de diálogo - CXXXIX

Benedicto XVI no necesitaba el escolasticismo

Aunque la formación inicial del joven Ratzinger en el seminario incluyó cursos sobre escolasticismo (después de todo, era obligatorio para los seminaristas en todo el mundo católico), evidentemente no tuvo ningún impacto en su mente. Describió su formación como “completamente orientada bíblicamente, trabajando desde la Sagrada Escritura, los Padres y la liturgia”, y agregó que “fue ecuménica”.

Admitió descaradamente: “Faltaba la dimensión filosófica tomista; tal vez ese fue el verdadero beneficio”.1

Deformación filosófica

Pero el tomismo no había simplemente “desaparecido” de la formación intelectual de Ratzinger: fue deliberadamente eliminado de su mente por su mentor teológico en el seminario mayor de Freising, con el resultado de que desde entonces lo evitó cuidadosamente como si fuera una plaga. Lo aabemos por el testimonio de su amigo de toda la vida, el P. Alfred Läpple, quien acogió al joven Ratzinger bajo su protección y ejerció en él una influencia formativa. Así lo reconoció más tarde Ratzinger cuando era Prefecto de la Congregación para la Doctrina de la Fe.2

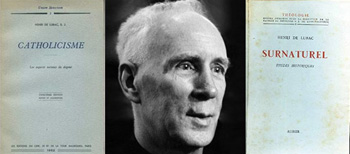

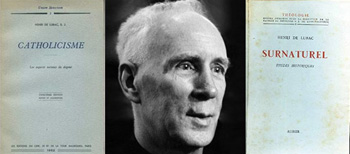

En una reveladora entrevista,3 el P. Läpple amplió su relación. Pasaban mucho tiempo juntos discutiendo la “Nueva Teología” en sus frecuentes paseos, que Ratzinger disfrutaba inmensamente. Fue durante estas ocasiones que el P. Läpple lo animó a adoptar un enfoque neomodernista de la Fe, que marcaría su perspectiva durante el resto de su carrera. Fue él quien le presentó las obras de Henri De Lubac SJ, Lo sobrenatural:

En una reveladora entrevista,3 el P. Läpple amplió su relación. Pasaban mucho tiempo juntos discutiendo la “Nueva Teología” en sus frecuentes paseos, que Ratzinger disfrutaba inmensamente. Fue durante estas ocasiones que el P. Läpple lo animó a adoptar un enfoque neomodernista de la Fe, que marcaría su perspectiva durante el resto de su carrera. Fue él quien le presentó las obras de Henri De Lubac SJ, Lo sobrenatural:

“Se las di pensando que sería una agradable sorpresa. Y de hecho, escribe en su autobiografía, que se convirtió para él en un libro de referencia y le ofreció una nueva relación con el pensamiento de los Padres, pero también un nuevo punto de vista sobre la teología. De hecho, más de un tercio del libro estaba compuesto por citas de los Padres”.4

Ratzinger quedó instantáneamente impresionado por esta obra de De Lubac y estaba ansioso por leer toda su œuvre. Su admiración por su “héroe” era ilimitada y expresó su sentimiento de deuda:

“En el otoño de 1949, Alfred Lapple me había regalado El catolicismo, quizás la obra más significativa de Henri de Lubac, en la magistral traducción de Hans Urs von Balthasar. Este libro fue para mí un evento de lectura clave. Me dio no sólo una conexión nueva y más profunda con el pensamiento de los Padres, sino también una nueva manera de ver la teología y la fe como tales”.5

Pero ese “nuevo camino” propuesto por De Lubac fue censurado por Roma y denunciado por Pío XII en Mystici Corporis como un “falso misticismo” corrosivo de la verdadera Fe. No hace falta decir que De Lubac, cuya formación en el seminario dejaba mucho que desear, también dejó de lado la filosofía y la teología escolásticas en favor de los estudios bíblicos y patrísticos.

Pero ese “nuevo camino” propuesto por De Lubac fue censurado por Roma y denunciado por Pío XII en Mystici Corporis como un “falso misticismo” corrosivo de la verdadera Fe. No hace falta decir que De Lubac, cuya formación en el seminario dejaba mucho que desear, también dejó de lado la filosofía y la teología escolásticas en favor de los estudios bíblicos y patrísticos.

Con modelos a seguir como estos, no es sorprendente que Ratzinger desarrollara una temprana aversión a cualquier cosa que oliera a escolasticismo o que surgiera de la “tradición manualista”. En cambio, lo persuadieron de acudir directamente a la Biblia y a los Padres de la Iglesia como fuente teológica preferida.

El P. Läpple mostró cómo Ratzinger era impermeable a las enseñanzas escolásticas del profesor de Filosofía de Freising, Arnold Wilmsen, a cuyas conferencias asistía:

“Las conferencias de Wilmsen se escurrieron como el agua de un impermeable. Me dijo: lamento el tiempo que estoy perdiendo, sería mucho más útil salir a caminar contigo”.

Los efectos de esta educación deficiente se hicieron evidentes en su producción teológica posterior, como profesor, cardenal y Papa, que se caracterizó en gran medida por el neomodernismo.

El P. Läpple explicó: “Siempre le ha inquietado el impulso de considerar la verdad como una posesión que hay que defender. No se sentía cómodo con las definiciones neoescolásticas que le parecían baluartes, según las cuales lo que está dentro de la definición es la verdad y lo que está fuera es todo erróneo”.

El P. Läpple explicó: “Siempre le ha inquietado el impulso de considerar la verdad como una posesión que hay que defender. No se sentía cómodo con las definiciones neoescolásticas que le parecían baluartes, según las cuales lo que está dentro de la definición es la verdad y lo que está fuera es todo erróneo”.

Pero la Iglesia siempre ha afirmado haber poseído la verdad desde los inicios del cristianismo y la ha defendido a toda costa, hasta la muerte si fuera necesario. Es reveladora la objeción de Ratzinger a las “murallas de las definiciones neoescolásticas” que habían sostenido la fe católica mediante “fórmulas fijas”. Para los herederos modernistas de nuestros días, la fe y todas sus manifestaciones (doctrina y liturgia) nunca alcanzan una verdad fija, sino que evolucionan continuamente.

Las “murallas” también fueron el objetivo favorito de los colegas progresistas de Ratzinger, el P. Urs von Balthasar, por ejemplo6 identificó la escolástica como una de las murallas que había que derribar. Después de describirse a sí mismo como “languideciendo en el desierto del neoescolasticismo”, se imaginaba, perversamente, como un Sansón moderno que derribaba la casa de los filisteos (tradicionalistas):

“Todo mi período de estudio en la Compañía de Jesús fue una lucha sombría con la monotonía de la teología, con lo que los hombres habían hecho de la gloria de la revelación. No pude soportar esta presentación de la Palabra de Dios y quise arremeter con la furia de un Sansón: sentí ganas de derribar, con las propias fuerzas de Sansón, todo el templo y sepultarme bajo los escombros. Pero fue así porque, a pesar de mi sentido de vocación, quería llevar a cabo mis propios planes y vivía en un estado de indignación sin límites.”7

Los esfuerzos de Balthasar contribuyeron significativamente al colapso de la apologética, la certeza moral y la instrucción catequética, por nombrar sólo algunas víctimas de sus impulsos iconoclastas.

Consecuencias de arrasar los baluartes

Sin una defensa razonada de la Fe que señale la distinción entre cosas como la verdad y el error, el bien y el mal, la naturaleza y la gracia, la carne y el Espíritu, los fieles rápidamente se sumergen en un marasmo de teorías confusas propugnadas por la neoconciencia de los modernistas de hoy. Como resultado, muchos católicos hoy han perdido la capacidad de distinguir entre el bien y el mal a los ojos de Dios.

Nadie puede negar que esta es la situación actual a la que nos enfrentamos, donde la gente mezcla la realidad con emociones que luego se convierten para ellos en el estándar de la verdad. Sin embargo, hace sólo unas décadas a todos se les enseñó (desde la “tradición manualista”) que aceptar la Revelación era asentir a una verdad o conjunto de verdades debido a la autoridad reveladora de Dios, y que lo que se requería del creyente era la sumisión y homenaje de su intelecto y su voluntad.

La cruzada de Ratzinger contra el escolasticismo

Desde su juventud como seminarista hasta el final de su vida, Ratzinger nunca asumió la responsabilidad del sistema escolástico que era central en la tradición teológica católica. Esta fue una ruptura importante con la política de los Papas anteriores al Vaticano II. Estaba claro que a él mismo no le servía de nada. Eso no significa que nunca reconoció sus puntos fuertes, pero en las raras ocasiones en que elogió la tradición, lo hizo como una formalidad, de una manera distante, calculada y desprovista de cualquier calidez personal.

Por ejemplo, en 2009 afirmó que “al leer las summae escolásticas uno queda impresionado por el orden, la claridad y la continuidad lógica de los argumentos y por la profundidad de ciertas ideas”.8 Pero esto fue simplemente un elogio débil, porque sus palabras no fueron acompañadas por ninguna convicción de que debería servir a un propósito útil en la Iglesia como un método importante –incluso indispensable– para explicar y preservar la fe.

No es sólo que Ratzinger pensara que la escolástica era irrelevante en la era moderna; Incomprensiblemente, lo consideró una amenaza letal a la supervivencia de la fe católica, una amenaza que sentía que era su deber combatir. En 1971 escribió un artículo que fue publicado en un libro de ensayos editado por Karl Rahner, en el que afirmaba:

No es sólo que Ratzinger pensara que la escolástica era irrelevante en la era moderna; Incomprensiblemente, lo consideró una amenaza letal a la supervivencia de la fe católica, una amenaza que sentía que era su deber combatir. En 1971 escribió un artículo que fue publicado en un libro de ensayos editado por Karl Rahner, en el que afirmaba:

“Quiero subrayar una vez más que estoy decididamente de acuerdo con [Hans] Küng cuando hace una distinción clara entre la teología romana (enseñada en las escuelas de Roma) y la fe católica. Liberarse de las cadenas restrictivas de la teología escolástica romana representa un deber del que, en mi humilde opinión, parece depender la posibilidad de la supervivencia del catolicismo”.9

No podemos dejar de notar el trasfondo subversivo de este polémico pasaje. Su objetivo era separar la teología católica del mismo sistema que la sustentaba, dejándola indefensa contra los ataques, basándose en que la Verdad puede valerse por sí misma y no necesita ser defendida por medio de “salvaguardias externas”. Poco antes de convertirse en Papa, Ratzinger reiteró este punto:

“¿Pero no podría ser reprochada a ella [la Iglesia] por haber llevado las riendas con demasiada fuerza, por haber creado demasiadas leyes, dado que no pocas de ellas contribuyeron a abandonar el siglo a la incredulidad en lugar de salvarlo? En otras palabras, ¿no podría ser reprendida por confiar demasiado poco en el poder de la verdad que vive y triunfa en la fe, por atrincherarse detrás de salvaguardas exteriores en lugar de confiar en la verdad, que es inherente a la libertad y evita tales defensas? 10

Una característica de la perspectiva optimista del Vaticano II era que el hombre moderno, cada vez más consciente de su “dignidad humana”, se volvería naturalmente hacia la verdad. Ése fue el mensaje contenido en el discurso inaugural pronunciado por Juan XXIII pero influido, como hemos visto, por el propio Ratzinger. El corolario del mensaje fue que la gente hoy disfruta de una libertad sin precedentes y no necesita que la Iglesia les imponga pronunciamientos infalibles, especialmente en el Nombre de Dios.

Para los católicos, sin embargo, la meta más alta no es la libertad, sino el logro de la Verdad en medio de las trampas del diablo y las aflicciones de la naturaleza humana caída, que es exactamente lo que los Manuales Escolásticos les ayudaban a lograr.

Continuará

Admitió descaradamente: “Faltaba la dimensión filosófica tomista; tal vez ese fue el verdadero beneficio”.1

Deformación filosófica

Pero el tomismo no había simplemente “desaparecido” de la formación intelectual de Ratzinger: fue deliberadamente eliminado de su mente por su mentor teológico en el seminario mayor de Freising, con el resultado de que desde entonces lo evitó cuidadosamente como si fuera una plaga. Lo aabemos por el testimonio de su amigo de toda la vida, el P. Alfred Läpple, quien acogió al joven Ratzinger bajo su protección y ejerció en él una influencia formativa. Así lo reconoció más tarde Ratzinger cuando era Prefecto de la Congregación para la Doctrina de la Fe.2

El P. Alfred Läpple inició al joven Ratzinger en el progresismo, este neomodernismo

“Se las di pensando que sería una agradable sorpresa. Y de hecho, escribe en su autobiografía, que se convirtió para él en un libro de referencia y le ofreció una nueva relación con el pensamiento de los Padres, pero también un nuevo punto de vista sobre la teología. De hecho, más de un tercio del libro estaba compuesto por citas de los Padres”.4

Ratzinger quedó instantáneamente impresionado por esta obra de De Lubac y estaba ansioso por leer toda su œuvre. Su admiración por su “héroe” era ilimitada y expresó su sentimiento de deuda:

“En el otoño de 1949, Alfred Lapple me había regalado El catolicismo, quizás la obra más significativa de Henri de Lubac, en la magistral traducción de Hans Urs von Balthasar. Este libro fue para mí un evento de lectura clave. Me dio no sólo una conexión nueva y más profunda con el pensamiento de los Padres, sino también una nueva manera de ver la teología y la fe como tales”.5

Ratzinger estuvo fuertemente influenciado por los libros condenados de De Lubac

Con modelos a seguir como estos, no es sorprendente que Ratzinger desarrollara una temprana aversión a cualquier cosa que oliera a escolasticismo o que surgiera de la “tradición manualista”. En cambio, lo persuadieron de acudir directamente a la Biblia y a los Padres de la Iglesia como fuente teológica preferida.

El P. Läpple mostró cómo Ratzinger era impermeable a las enseñanzas escolásticas del profesor de Filosofía de Freising, Arnold Wilmsen, a cuyas conferencias asistía:

“Las conferencias de Wilmsen se escurrieron como el agua de un impermeable. Me dijo: lamento el tiempo que estoy perdiendo, sería mucho más útil salir a caminar contigo”.

Los efectos de esta educación deficiente se hicieron evidentes en su producción teológica posterior, como profesor, cardenal y Papa, que se caracterizó en gran medida por el neomodernismo.

El P. Hans Urs von Balthasar quería destruir las murallas del escolasticismo

Pero la Iglesia siempre ha afirmado haber poseído la verdad desde los inicios del cristianismo y la ha defendido a toda costa, hasta la muerte si fuera necesario. Es reveladora la objeción de Ratzinger a las “murallas de las definiciones neoescolásticas” que habían sostenido la fe católica mediante “fórmulas fijas”. Para los herederos modernistas de nuestros días, la fe y todas sus manifestaciones (doctrina y liturgia) nunca alcanzan una verdad fija, sino que evolucionan continuamente.

Las “murallas” también fueron el objetivo favorito de los colegas progresistas de Ratzinger, el P. Urs von Balthasar, por ejemplo6 identificó la escolástica como una de las murallas que había que derribar. Después de describirse a sí mismo como “languideciendo en el desierto del neoescolasticismo”, se imaginaba, perversamente, como un Sansón moderno que derribaba la casa de los filisteos (tradicionalistas):

“Todo mi período de estudio en la Compañía de Jesús fue una lucha sombría con la monotonía de la teología, con lo que los hombres habían hecho de la gloria de la revelación. No pude soportar esta presentación de la Palabra de Dios y quise arremeter con la furia de un Sansón: sentí ganas de derribar, con las propias fuerzas de Sansón, todo el templo y sepultarme bajo los escombros. Pero fue así porque, a pesar de mi sentido de vocación, quería llevar a cabo mis propios planes y vivía en un estado de indignación sin límites.”7

Los esfuerzos de Balthasar contribuyeron significativamente al colapso de la apologética, la certeza moral y la instrucción catequética, por nombrar sólo algunas víctimas de sus impulsos iconoclastas.

Consecuencias de arrasar los baluartes

Sin una defensa razonada de la Fe que señale la distinción entre cosas como la verdad y el error, el bien y el mal, la naturaleza y la gracia, la carne y el Espíritu, los fieles rápidamente se sumergen en un marasmo de teorías confusas propugnadas por la neoconciencia de los modernistas de hoy. Como resultado, muchos católicos hoy han perdido la capacidad de distinguir entre el bien y el mal a los ojos de Dios.

Nadie puede negar que esta es la situación actual a la que nos enfrentamos, donde la gente mezcla la realidad con emociones que luego se convierten para ellos en el estándar de la verdad. Sin embargo, hace sólo unas décadas a todos se les enseñó (desde la “tradición manualista”) que aceptar la Revelación era asentir a una verdad o conjunto de verdades debido a la autoridad reveladora de Dios, y que lo que se requería del creyente era la sumisión y homenaje de su intelecto y su voluntad.

La cruzada de Ratzinger contra el escolasticismo

Desde su juventud como seminarista hasta el final de su vida, Ratzinger nunca asumió la responsabilidad del sistema escolástico que era central en la tradición teológica católica. Esta fue una ruptura importante con la política de los Papas anteriores al Vaticano II. Estaba claro que a él mismo no le servía de nada. Eso no significa que nunca reconoció sus puntos fuertes, pero en las raras ocasiones en que elogió la tradición, lo hizo como una formalidad, de una manera distante, calculada y desprovista de cualquier calidez personal.

Por ejemplo, en 2009 afirmó que “al leer las summae escolásticas uno queda impresionado por el orden, la claridad y la continuidad lógica de los argumentos y por la profundidad de ciertas ideas”.8 Pero esto fue simplemente un elogio débil, porque sus palabras no fueron acompañadas por ninguna convicción de que debería servir a un propósito útil en la Iglesia como un método importante –incluso indispensable– para explicar y preservar la fe.

Kung y Ratzinger: ambos comprometidos con el cambio

“Quiero subrayar una vez más que estoy decididamente de acuerdo con [Hans] Küng cuando hace una distinción clara entre la teología romana (enseñada en las escuelas de Roma) y la fe católica. Liberarse de las cadenas restrictivas de la teología escolástica romana representa un deber del que, en mi humilde opinión, parece depender la posibilidad de la supervivencia del catolicismo”.9

No podemos dejar de notar el trasfondo subversivo de este polémico pasaje. Su objetivo era separar la teología católica del mismo sistema que la sustentaba, dejándola indefensa contra los ataques, basándose en que la Verdad puede valerse por sí misma y no necesita ser defendida por medio de “salvaguardias externas”. Poco antes de convertirse en Papa, Ratzinger reiteró este punto:

“¿Pero no podría ser reprochada a ella [la Iglesia] por haber llevado las riendas con demasiada fuerza, por haber creado demasiadas leyes, dado que no pocas de ellas contribuyeron a abandonar el siglo a la incredulidad en lugar de salvarlo? En otras palabras, ¿no podría ser reprendida por confiar demasiado poco en el poder de la verdad que vive y triunfa en la fe, por atrincherarse detrás de salvaguardas exteriores en lugar de confiar en la verdad, que es inherente a la libertad y evita tales defensas? 10

Una característica de la perspectiva optimista del Vaticano II era que el hombre moderno, cada vez más consciente de su “dignidad humana”, se volvería naturalmente hacia la verdad. Ése fue el mensaje contenido en el discurso inaugural pronunciado por Juan XXIII pero influido, como hemos visto, por el propio Ratzinger. El corolario del mensaje fue que la gente hoy disfruta de una libertad sin precedentes y no necesita que la Iglesia les imponga pronunciamientos infalibles, especialmente en el Nombre de Dios.

Para los católicos, sin embargo, la meta más alta no es la libertad, sino el logro de la Verdad en medio de las trampas del diablo y las aflicciones de la naturaleza humana caída, que es exactamente lo que los Manuales Escolásticos les ayudaban a lograr.

Continuará

- Benedict XVI with Peter Seewald, Last Testament, p. 83.

- In a letter to Fr. Läpple dated June25, 1995, Card. Ratzinger thanked him for providing essential support in his philosophical and theological journey at the beginning of his academic career. (J. Ratzinger, ‘Tu sei all’inizio del mio cammino filosofico-teologico,’ 30 Days, February 1, 2006).

- Gianni Valente and Pierluca Azzaro, “That new beginning that bloomed among the ruins: Inteview with Alfred Läpple,” 30 Days, February 1, 2006.

- Ibid.

- Joseph Ratzinger, Milestones: Memoirs 1927-1977, trans. Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1998, p. 98.

- Urs von Balthasar, Razing the Bastions: On the Church in This Age, trans. Brian McNeil, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1993

- Peter Henrici SJ, “Hans Urs von Balthasar: A Sketch of His Life,” Communio, vol. 16, Fall 1989, p. 313. Note 15 gives the original source as the Introduction by Hans Urs von Balthasar (ed.) to Adrienne von Speyr, Erde und Himmel. Ein Tagebuch (Earth and Heaven: a Diary), Part 2, Die Zeit der Grossen Dictate (The Age of the Great Dictates), Einsiedeln: Johannes Verlag, 1975, p. 195. Fr. Henrici was von Balthasar’s nephew, and Adrienne von Speyr was his close companion and inspiration.

- Benedict XVI, “Monastic Theology and Scholastic Theology,”, General Audience, St Peter’s Square, October 28, 2009.

- J. Ratzinger, “Widersprüche im Buch von Hans Küng” (Contradictions in Hans Küng’s Book), Stimmen der Zeit (Contemporary Voices), (ed. Karl Rahner), vol. 187, Freiburg: Herder, 1971, pp. 97-116.

- J. Ratzinger, The Ratzinger Reader: Mapping a Theological Journey, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010, p. 212.

Publicado el 11 de junio de 2024

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |